If Iceland can be successful in the Euro Cup, why can’t #USMNT compete in Copa?

As Karni Arnason leapt over Wayne Rooney and headed the ball onto Ragnar Sigurdsson’s foot, he didn’t just get the game-tying assist. He also made American history. Way back in the early 2000s, Arnason was a college kid. He played … Continued

As Karni Arnason leapt over Wayne Rooney and headed the ball onto Ragnar Sigurdsson’s foot, he didn’t just get the game-tying assist. He also made American history.

Way back in the early 2000s, Arnason was a college kid. He played two years for Gonzaga (this was around the same time Ronny Turiaf was destroying the WCC for the basketball Bulldogs, if you want to feel old) and one over on Long Island at Adelphi before turning pro. His assist was the first point scored at the European championships by a former NCAA athlete. Yes, it would seem that between the #Brexit jokes and the #IcelandSmites zingers about ancient Edda mythos, Iceland has carved out a model for success that eluded the Yanks this summer.

Arnason isn’t just a national hero or an against-all-odds success story. He’s forcing a whole other conversation than the one going on inside his continent, in his tournament. If Iceland can fold ex-NCAA stars like Arnason into their identity, does that mean that the American system works? And if so, why doesn’t it seem to work for America?

The 33-year-old Malmö man isn’t the only Icelander to take advantage of NCAA ball. There have been dozens of men who have come west to play. Women too; Dagny Brynjarsdottir was a 4-year star at Florida State University and now plays for the NWSL Portland Thorns. At 24, she already has 61 caps for Iceland.

And as for Iceland’s success? It’s hardly a blip. As Brian Blickenstaff detailed, manager Lars Lagerback took over a promising side in 2011 and led them to the brink of World Cup 2014 qualification before seeing them breeze through Euro qualification. The youngest member of this squad, Johann Berg Gudmundsson, is 25 and has been with the senior team for eight years.

It doesn’t work here for many reasons, first and foremost being: which American has five years to wait until qualification? Lagerback was given carte blanche to inculcate a culture, preach organization and name a successor in Heimir Hallgrimsson. Or in other words, Lagerback became Iceland’s coach two months after Jurgen Klinsmann took over the American job but faced far less pressure.

While we’re all waiting for the Klinsmann-era postmortem to understand what worked and what didn’t, it is pretty clear what is working for Lagerback: organization, organization, organization. “By focusing on being the best-organized team in the world,” Blickenstaff wrote, “the players were absolved of [any] inferiority complex” that might come with being an island nation of 350,000 people.

Americans don’t have to have too long a memory to think about a coach that focused on organization and identity to overcome a minnow mentality. Bob Bradley used a similar approach to get a shaky squad to the knockout rounds of the 2010 World Cup.

But Bradley was a goner a year later, and Jurgen Klinsmann was hired in many ways because he represented Bradley’s opposite. American soccer has since learned precisely what the opposite of “organization” looks like.

A few months ago, Will Parchman compared the US development system to an octopus, and not because of its flexibility and smarts. “This is the organism responsible for youth soccer development in America today,” he wrote. “And it is every bit as slippery, complicated, and prone to working at cross-purposes as that octopus groping its way through the darkness.” A variety of youth academies, college teams, and Major League Soccer are all vying to produce the best players to sell to the highest bidder.

It’s worth reading Parchman’s detailed description for two reasons. First, the scale of this problem is incredible — and a far cry from the structure that could be put in place in Iceland. In US soccer, hundreds of stakeholders who are certain that their idiosyncratic ways are the best ways to make American soccer better must be aligned. It’s a PTA meeting, but for sports.

Second, Klinsmann is also Technical Director for the US Soccer Federation. One of his many, many, roles was to fix the exact problems that Parchman laid out. There has been plenty of talk under this management about a re-imagining of the US soccer pyramid, but it hasn’t happened. It is certainly not all the fault of one sandy-haired German because again, hundreds of stakeholders across the country. But MLS, NCAA, and youth soccer are still working at cross-purposes. That doesn’t even include the German dual-nationals or EU passport holders like Christian Pulisic.

If there is a plan in place and not just a mission statement, it is unclear if anyone in America has seen it. As for Iceland, this is a half-decade’s worth of plans coming to fruition. Plans that are straightforward enough to stick to an identity, but flexible enough to find room for tall old trees like Karni Arnason. Countries like Chile and Italy have plans too, of course. But they also have decades of experience and wide margins for error.

The United States and Iceland have to both strategize for when things go wrong and hope everything goes right. This summer, we’ve seen only one of those countries have it all work out according to plan.

This post was composed by freelance writer and swell guy, Asher Kohn. Reach out to him and discuss all the soccer happenings from around the world on Twitter at:@AJKhn. Catch up with all of the latest soccer/footie/futbol/fußball/deild news on SiriusXM FC.

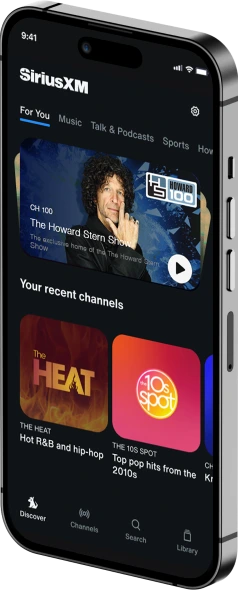

Music, Sports, News and more

All in one place on the SiriusXM app